Keep up-to-date on the

latest from Dead Oceans

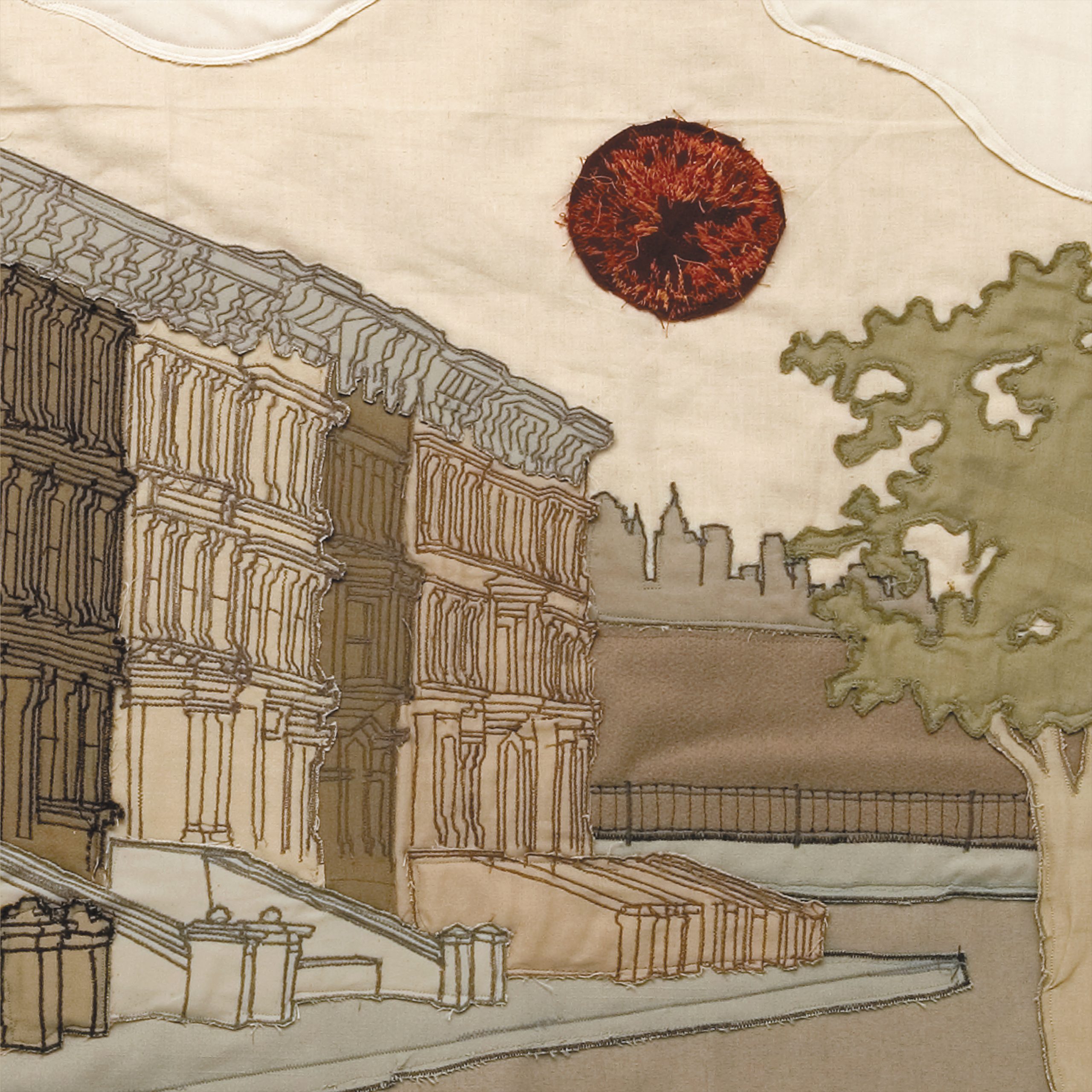

Bright Eyes

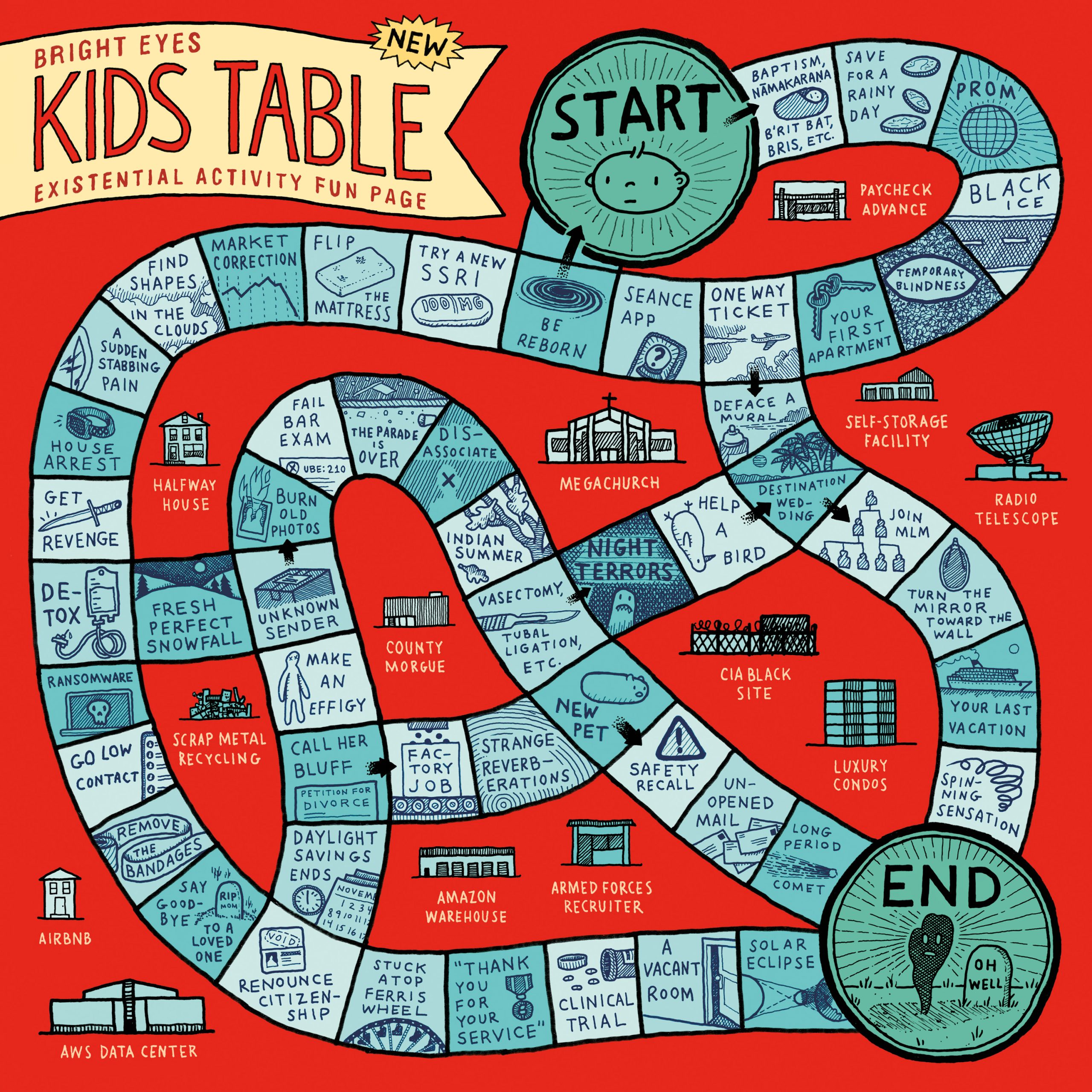

Down in the Weeds, Where the World Once Was

1. Pageturners Rag

2. Dance And Sing

3. Just Once In The World

4. Mariana Trench

5. One And Done

6. Pan And Broom

7. Stairwell Song

8. Persona Non Grata

9. Tilt-A-Whirl

10. Hot Car In The Sun

11. Forced Convalescence

12. To Death's Heart (In Three Parts)

13. Calais To Dover

14. Comet Song

As a title, as a thesis, Down in the Weeds, Where the World Once Was functions on a global, apocalyptic level of anxiety that looms throughout the record. But on a personal level, it speaks to rooting around in the dirt of one’s memories, trying to find the preciousness that’s overgrown and unrecognizable. For Conor Oberst, coming back to Bright Eyes was a bit of that. A symbol of simpler times, vaguely nostalgic. And even though it wasn’t actually possible to go back to the way things were, even though there wasn’t an easy happy ending, there was a new reality left to work with.

In 2011 the release of The People’s Key, Bright Eyes’ ninth and most recent album, ushered in an unofficial hiatus for the beloved project. In the time since, the work of the band’s core members – Oberst, multi-instrumentalist Mike Mogis, and multi-instrumentalist Nathaniel Walcott – has remained omnipresent, through both the members’ original work and collaboration. The friendship remained solid and their projects overlapped from time to time, with Oberst and Mogis living next door to one another in Omaha and Walcott’s Los Angeles home just fifteen minutes away from Oberst’s house on the East Side, where he’s spent the bulk of his time over the last few couple of years whilst working on his most recent solo records and Better Oblivion Community Center.

The end of Bright Eyes’ unofficial hiatus came naturally. Oberst pitched the idea of getting the band back together during a 2017 Christmas party at Walcott’s house. The two huddled in the bathroom and called Mogis, who was Christmas shopping at an Omaha mall. Mogis immediately said yes. The resulting Bright Eyes album came together unlike any other of its predecessors. Down in the Weeds is Bright Eyes’ most collaborative, stemming from only one demo and written in stints in Omaha and in bits and pieces in Walcott’s home. Radically altering a writing process 25 years into a project seems daunting, but Oberst said there was no trepidation: “Our history and our friendship, and my trust level with them, is so complete and deep. And I wanted it to feel as much like a three-headed monster as possible.”

In spite of all its newness, the LP feels like the most complete amalgamation of Bright Eyes. The symphony’s presence recalls Walcott’s orchestral arrangements on Cassadaga, while hyper-percussive elements and effects conjure Digital Ash. The jolting intimacy of Oberst’s singular voice and its folk songwriting core are the same foundations of Lifted and I’m Wide Awake. And overblown acoustic guitar marks Mogis’ production reaching back in time to the original recordings Oberst made on a 4-track 25 years ago.

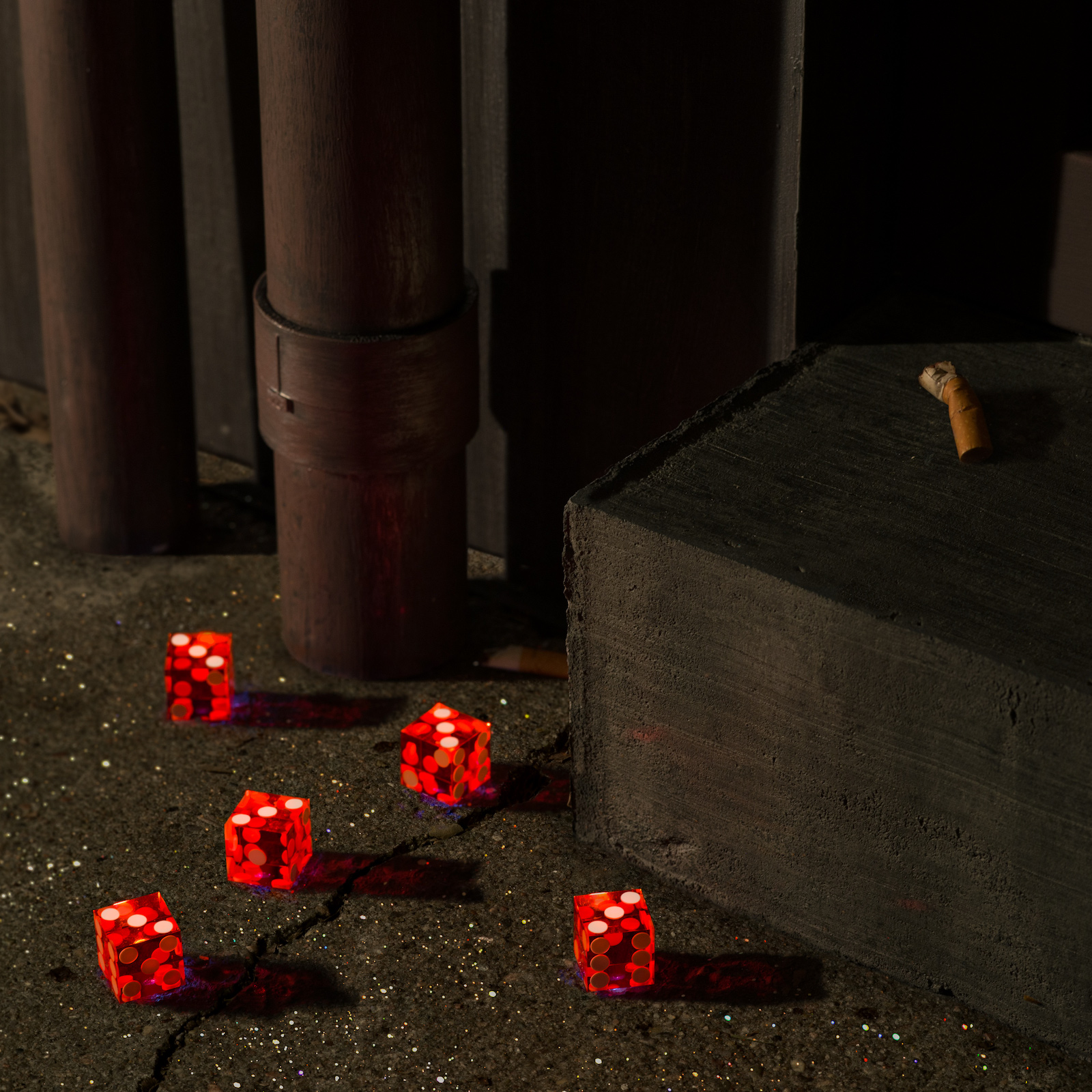

Across recording sessions between Omaha’s ARC Studios, Los Angeles’s Electro-Vox, and LA’s Capitol Studios, the trio leaned into experimentation, yielding an ambitious, musically inventive LP. Aside from the surprising rhythm section made up of the fierce musicianship of Jon Theodore (Mars Volta, Queens of the Stone Age, One Day as a Lion) and the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Flea, the compositions expand the expectation of what Bright Eyes’ sound is.

Down in the Weeds, Where the World Once Was is an enormous record caught in the profound in-between of grief and clarity – one arm wrestling it’s demons, the other gripping the hand of love, in spite of it.